Written by Annalise Mabe and Mariette Williams

Photos by Adrian O’Farrill

Though visitors to Tampa are drawn to its sleek new hotels, trendy restaurants, and luxe retail stores, the city’s historical and cultural roots can be traced back to the red-brick roads of Ybor City, and the people who built it.

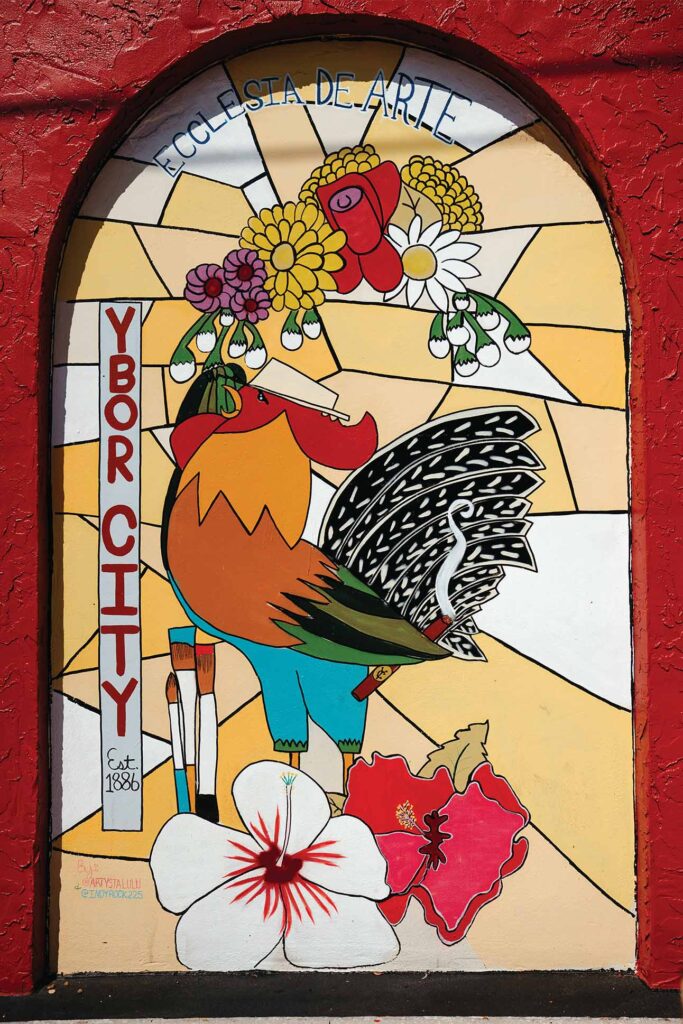

Named after its founder, cigar-maker Vincente Martinez Ybor, Ybor City was founded in 1885 and attracted Cuban, Italian, and Spanish immigrants who found work in cigar rolling, and homes, or casitas, provided to workers at cost. It was here where the Cuban sandwich was born, where liquor was bootlegged, races rigged, and where some of the finest hand-rolled cigars are still made today.

Ybor found that Tampa’s humidity and proximity to Cuba (where he imported tobacco from) was perfect, and he purchased 40 acres of land, setting up his cigar factory in the swampland. By the early 1900s, 200 factories were producing over a million cigars a day, earning Ybor City the name “Cigar City.”

Down North 16th Street, El Reloj, a three-story brick clock tower that spans one city-block long is home to J.C. Newman Cigar Co., America’s oldest family-owned premium cigar company, and the last operating cigar factory in Tampa, Florida.

Holden Rasmussen, the factory’s resident historian, confirms.

“We’re Ybor City’s last premium cigar factory,” says Rasmussen. “Competitors were either consolidated or moved overseas. Cigar City, U.S.A., baby. Fifteen million cigars a year, handmade and made by 70-year-old, hand-operated machines.”

Julius Caesar Newman, founder of the company, hailed from Slovakia and set up shop rolling cigars with $50 worth of tobacco and a handmade cigar table in his Cleveland basement with his cousins being his first employees. The family grocer was his first customer. Newman fell in love with Cuban tobacco and knew he had to make a move.

“Everyone knew that if you wanted a really good cigar, it had to be pure Cuban,” Rasmussen says.

And so, Newman moved the company to Tampa and into El Reloj, the clock tower factory, because Tampa had the best Cuban tobacco and a flourishing Cuban community.

“Everything you needed was right down the street,” Rasmussen says. “If you were a kid just getting out of school and you needed to go meet grandma, you’d walk over to El Reloj where she’d be getting done with her shift, hand-rolling cigars.”

The 113-year-old building is frozen in time and operates exactly as it has for the past 70 years. The original wood floors are somehow still sturdy, the original brick, still strong. Even the clock tower still rings.

Outside, a population of 500 chickens and roosters (originally kept by Cubans) still roam wild and are protected by the city and supported by the Ybor Misfits Micro sanctuary, a small, volunteer-run chicken rescue.

But back inside, Rasmussen takes visitors down to a warm, muggy basement, to the vault that smells of caramel, nuts, and wood.

“We were a mob town once upon a time,” he explains.

“They’d rig the races and run rum up the states. If we didn’t want to get robbed, we had to use this trap door,” he says, opening a small wooden door at the end of a narrow hallway. “It’s a testament to how long we’ve been in the game.”

When Prohibition took effect in January 1920, Ybor City was home to roughly 76 saloons which outlawed overnight. The result of the law that prohibited the sale, production, or transportation of alcohol were speakeasies that sprung up along 7th Avenue in Ybor City. One of the most famous speakeasies was The Eagle Club, also known as the Key Club. Membership was invite-only, and prospective members had to be interviewed to certify their financial and social standing. Once members were admitted, they were given a key that would unlock a door at street level that led to a second door where a secret password had to be uttered to enter.

In the basement’s vault, Rasmussen shows off a giant cigar made for the King of Spain back in the ‘20s, a King cigar, and some pre-embargo Cuesta Reys. He starts to whisper because a news crew is nearby, getting B-roll of the oldest hand-rolled cigars in the world that live here.

On the second floor, a cellophane machine from 1947 wraps cigars in shiny plastic. The second floor is straight out of the 1950s, and in another room, Rasmussen stands in front of a long room with rows and rows of brown rusted, mint green hand-operated machines, men and women sitting at them, pumping out wrappers for precise slicing.

“The machines are old school,” Rasmussen says. “If these break, they can be really difficult and expensive to fix.

On the third and top floor, six hand rollers sit at wooden cigar-rolling tables.

Ybor City’s historic district includes roughly 950 buildings, many of which are on the U.S. Register for Historical Places, and a stroll through the neighborhood promises cobblestone streets, charming casitas, and wrought iron balcony storefronts reminiscent of architecture found in New Orleans. Many of Ybor City’s original cigar factories, parlors, and theaters are still standing, a testimony to the visionaries who built the city.

There’s plenty of new life in Ybor City, too. The recently opened Hotel Haya is named after cigar factory owner and pioneer, Ignacio Haya, and the property has thoughtful details that celebrate Haya’s legacy, including the hotel’s signature restaurant, Flor Fina, which translates to delicate flower, an inscription Haya would include in his cigar boxes.

Hotel Haya is also located on the former site of Ybor City’s first Cuban cafe, Las Novedades, which opened in 1890, and architects have preserved the building’s original interior and textiles. The rest of the property has a relaxed, boho design coupled with nostalgic touches like exposed brick walls, a courtyard pool featuring Italian tile, and a repurposed Haya sign—all tributes to Ybor City’s earliest pioneers.

Peter Wright, the hotel’s GM explains the dedication to preserving the city’s architectural history.

“For Las Novedades, an event space we are revitalizing, we’re really just getting it up to code and preserving all of its raw space, original brick, and stained-glass windows from the early 1900s,” he says. “It’s the little details—the replica Goya tiles we found behind the walls—that we want guests to enjoy when they experience this place.”

Wright also mentions the new Gas Worx project that officially began this year with the intent to connect Ybor City with the Channel District, utilizing the land to promote connectivity via multi-use trails and a new stop for the TECO streetcar.

“We’re all connected,” Wright says. “And this transit-oriented project will only connect us further. Two years from now you’re going to see a lot of change here, but you’ll also see the preservation of our history in the process.”